|

Kaller Historical Documents, Inc. | ||

| 732-617-7120 | |||

|

Home | About Us | Catalog | Collections | Exhibits | Contact Us | Policies |

|||

|

We build museum quality collections of historical autographs, manuscripts, letters, art & rare books |

|||

|

|

|

|

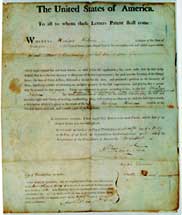

George

Washington Signed Patent for One of the First Improvements on Eli Whitney’s

Cotton Gin; Dated May 12, 1796 The patent has played a key role in the commercial and economic development of the United States. By protecting the rights of individual inventors, patents provide a necessary impetus for technological innovation. The American patent system has its origins in fourteenth century England, where literae patentes, or royal grants, were exclusive commercial rights issued to encourage commerce and industry, or to reward political favorites. An Italian inventor, Giacopo Acontio, applied for a patent in England for a furnace and “wheel-machines", and argued that “those who by searching have found out things useful to the public should have some fruits of their rights and labors." He added that unless his inventions were protected by the government, others would copy them to his loss. In 1559, England granted Acontio the first true patent protecting an invention. |

|

|

In seventeenth century North America, most grants were issued for the right to lease land or collect taxes. But as the New World developed into an organized and economically viable entity, there was a shift in patent distribution: Colonial governments in need of new industry started granting limited monopolies to individuals willing to pursue new or neglected manufactures. In addition, several states issued their own patents for mechanical inventions. The patents could not be enforced, however, as the constitution had not yet been ratified, and the law was not uniform throughout the colonies.

This changed in 1788, when the constitution charged Congress, “To promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries” (Article I, Section 8). Congress, in its second session of 1790, enacted the first patent law granting inventors exclusive rights to their work for a period of fourteen years. The first U.S. patent was issued on July 31, 1790 to Samuel Hopkins of Philadelphia for a method of making potash, an ingredient useful for soap making. The document is now housed at the Chicago Historical Society. The 1790 patent law also mandated that the president must sign each patent, and it established a board of cabinet officers that evaluated and issued patents to inventions worthy of protection. Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson, Secretary of War Henry Knox, and Attorney General Edmund Randolph made up the first and only cabinet board charged with evaluating the novelty of patents. The board soon realized that they were unable to devote the necessary time to evaluate each patent fairly. In 1793, Congress passed a new law charging the Secretary of State to issue patents to any applicant who complied with a set of prescribed formalities, leaving the courts to determine their validity.

Eli Whitney's Cotton Gin was an innovation that fell victim to an imperfect patent system, and the resulting ease with which competitors could pirate his invention. Though Whitney received a patent for the Cotton Gin in 1794, it failed to protect his invention. By 1797, Whitney's Cotton Gin business collapsed due to widespread piracy of his invention. Despite Whitney's demise, ambitious inventors continued to develop the Cotton Gin, hoping to claim a piece of what would become one of the greatest inventions in American history.

This document, which is a highlight of our Presidential Patent Collection, is signed by George Washington as President, Timothy Pickering as Secretary of State, Charles Lee as Attorney General, and the inventor Hodgen Holmes. This unusually rare patent documents Holmes' improvement to Eli Whitney's Cotton Gin (he replaced the spikes on Whitney’s machine with circular saws). Although many patents were issued for improvements on the Cotton Gin, Holmes' innovation is by far the most significant, and he is typically the only innovator historians mention by name (See Thomas Kingston Derry, A Short History of Technology). |

|

|

P. 1: Presidential

Patent Collection Introduction |

|

Home |

About

Kaller Historical Documents | Historical

Collections | Online

Catalog |

Historical

Exhibits | Links:

Historical Associations | Historical

Ads | Order

| Policies

| Contact

Us |

Alumni

Program | Sponsorship

Opportunities | Sitemap

Quick Search| African American| American President | Arts & Entertainment | Charleston & Fort Sumter Documents | Confederate Document | Declaration Signer |Famous Women: First Ladies | Finance | Judaica | Maritime | Military: Civil War, Revolutionary War | Misc. Americana | Presidential Patent |Religion | Science & Technology | Stocks | Supreme Court | World History | A | Space Collection